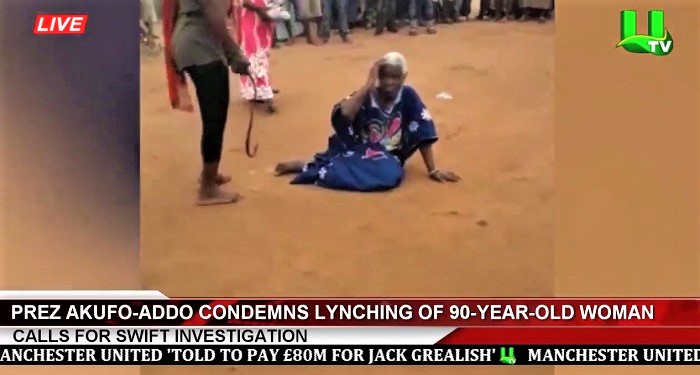

On July 23, 2020, Ghana succumbed to the traumatic news of a 90-year old woman who was stoned to death because she was accused of possessing witchcraft. Through the mediation of the new media, the video footage of the lynching of the woman received global attention.

The response was sporadic. Condemnation came from virtually everyone who had the chance of watching the video. For a while, we were shocked because we never thought such a barbaric act could happen in twenty-first century Ghana. Many of us had assumed that the “modern” world had no space for “superstition” and such a grotesque act.

It is, however, important to mention that our surprise was precisely because we thought that the pervasiveness of Christianity and the “modern” mechanisms of investigating the “mysteries” of life would dispel witchcraft and push it to the backwaters of history.

During the nineteenth century, the missionaries were intentional about suppressing any beliefs in the existence of powerful malevolent spirits. But as Birgit Meyer, a religious anthropologist who has written extensively on Pentecostal Christianity in Ghana, has observed the translation of the Bible into the various languages of the colonised people reinforced beliefs in the metaphysical world.

Instead of Christians dismissing or severing relationship with their ancestral past, the presentation of the spiritual forces in the indigenous world as the demons of the Bible became the aporia of mission work. This is because it revitalised the existential realities of the spiritual world of indigenous religion.

The missionaries emphasised a fusion of rationality and faith in Christ as the way of salvation. This led them to build schools, hospitals and founding of vocational schools, hoping that it would dissuade the indigenous people from making recourse to the religious functionaries of the indigenous religions.

But this approach towards mission work, framed as the 3Hs – Head (rational education), Heart (Gospel) and Hand (vocation) – did not appear to have made any significant impact.

This is to the extent that writing in the 1960s, K.A. Busia, Ghanaian academic and former Prime Minister of Ghana, after he assessed the impact of Christianity among the Akan he remarked that the religion was either superficial, alien or both. In sum, he said Christianity was like a thin veneer that did not interact well with Akan traditional religion.

Be as it may, just before the moratorium that marked the end of missionary activities in Ghana in postcolonial Africa in the 1960s, the rise of the African independent churches, including the Mosama Disco Christo Church (founded by Jemisimiham Jehu Appiah) and the Twelve Apostles (founded by Maame Harris Grace Tani and Papa Kwesi John Nackabah), responded the “impotence” of rationality in dealing with the African indigenous worldviews.

These figures incorporated practices such as exorcism and deliverance to deal with the malevolent spirits in the indigenous religions. They also sacralised the Bible as a living text that could ward off evil spirit. But in all of this, witchcraft was the main target of exorcistic exercise.

The rise of the Pentecostal movement in the early twentieth century through the instrumental role played by Peter Anim, regarded as the Father of Ghanaian Pentecostalism, and James McKeown, an Irish missionary who was in the Gold Coast in 1937, did not dispel the belief in witchcraft.

If for any reason at all, the Pentecostal movement reinforced the belief in witchcraft, except that it offered new approaches. The new approach discounted the use of religious items like Florida water, incense, and candles in exorcistic exercise.

Apostle Prof. Opoku Onyinah, the immediate chairman of the Church of Pentecost (2008-2018), Ghana’s largest protestant church, wrote his doctoral dissertation, submitted to the University of Birmingham, United Kingdom, on the preponderance of witchcraft in Ghana.

In his book, Pentecostal exorcism: Witchcraft and demonology in Ghana, he perceptively argued that in indigenous worldviews, “the principal evil is attributed to witchcraft since it is held that all evil forces can be in league with witches to effect an evil act” (Onyinah, 2012:1).

To corroborate Onyinah, in The Encyclopedia of witches, witchcraft & wicca, Rosemary Ellen Guiley, observed that “witches have never enjoyed a good reputation. Almost universally since ancient times, witchcraft has been associated with malevolence and evil. Witches are thought to be up to no good, interested in wreaking havoc and bringing misery to others” (Guiley, 2008: xi).

These observations are based on the non-binaries between the material and the immaterial worlds in most indigenous worlds. In many of the indigenous religions in Ghana and across the world, there is a fluid relationship between the physical and the metaphysical worlds. Spirits interpenetrate the two worlds and can impact on both worlds.

The fusion of the material and immaterial worlds leads to what is generally referred to as mystical causality in explaining an event. This means that nothing happens by accident. Everything must have a cause. Even if doctors provide a post-mortem report on the cause of death of a deceased person, most people will still probe to know the “why” of the death of the deceased.

For example, science was able to explain the cause of my father’s death that occurred on December 13, 2008. But because he was not visibly ill and died peacefully at home at the age of 65 years, some of my paternal relatives were not convinced about the outcome of the post-mortem that was done at the Ghana Police Hospital, Accra. They felt a witch had terminated my father’s life.

This belief in mystical causality is so strong because the work of a pathologist that uses a scientific approach to ascertain the cause of a person’s death answers the “how” questions and not the “why” questions.

It is this fixation for answers to the “why” questions that led Edward Evans Evans-Pritchard (an English anthropologist who studied the phenomenon of witchcraft among the Azande in Congo) to conclude that witchcraft has a certain logic, as it answers what is rationally or logically inexplicable.

The answer to the “why” questions is invested in the activities of witches. Witches are individuals who are able to utilise the powers invested in nature to exert impact on the material world. In some stories, witches are said to have the power to suck the blood of their victims. They are accused of causing all the sickness and evil in the world. Witches are believed to cause their victims to suffer mental psychosis.

Growing up in Maamobi, an urban slum in Accra, some of the religious functionaries told us that there was a tree at the what used to be called Montreal Park, where the Turkish government has sponsored the construction of the largest mosque in Ghana. As children, we were warned not to go near the huge baobab (known as “goji mayu” “witches’ tree) since it was believed to be the epicentre of witches in the community.

In the 1980s, words went around that the witches were responsible for frequent cases of convulsion among children in the community. Incidentally, just under the baobab tree was the place where some young men produced “ganda” (in Hausa) or “wele” (in other languages, including Twi). As children, playing under the baobab tree in the evening was not just fun, after the sun had set, but it was an adventure to get “ganda”.

Sadly, many children, including myself, suffered convulsion. Those days, partly because of the removal of subsidies on health, as a result of conditionalities of the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank, cash-and-carry (pay-as-you-go to receive healthcare) made it difficult for many people to access healthcare at the hospital.

And given that Maamobi is a low-income community, many people resorted to alternative forms of medication in the event of illness.

With the huge cost of receiving healthcare, children who suffered from convulsion were taken to religious functionaries (mallams – from mualim ‘teacher’) who had built speciality and reputation for treating convulsion.

So, when I suffered a convulsion, believed to have been caused by witches, I was taken to one such mallams, who made multiple incisions (three each) on some parts of my body, including the temples of my forehead, instep, knee, and breast and applied a black powder on them.

In the end, I was resuscitated, as my mother who then (in the early 1990s) belonged to one of the local African Independent churches, Prince of Peace, had prayed the mallam to keep making the incision.

According to my mother, I died, because the mallam almost gave up when I was not responding to the incision and the medicine that was applied. My late father concluded that I should just be given a simple burial. But as a mother, my mother felt more could be done to resuscitate me. Indeed, I survived the convulsion to write about witchcraft today.

In the 1960s, a major variety of secularization happened in history. This was the secularization of moral values. Instead of people turning to God through religious text as the source of moral values, the Bible, in particular, was trashed. Morality was relativized and at the behest of individuals.

People were free to determine their own version of moral values. So long as they did not interfere in the life of others, they were good to go. It was this period that witnessed the era of the sexual revolution, giving rise to all forms of sexual practices, including homosexuality.

Reflecting the moral climate in the 1960s, many scholars anticipated that the secularization of morality would consequently lead to the marginalization of institutional religion. Consequently, the popular scholarship, including the works of Peter Berger and Harvey Cox, at that time was that religion would run into recession as science and technology advanced.

It was also believed that superstitious beliefs, including the belief in witchcraft, would fade away. If religion was to survive at all, it was expected to be liberal and not emphasising fundamentalism or evangelicalism.

The predictions of these secularization scholars did not materialise especially following the Iranian revolution in 1979. The Iranian revolution, staged by Shia cleric Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini did not only affect the political temperature of the Arab world, especially with the overthrow of the liberal Shah government, led by Mohammed Reza Pahlavi. It led to the resurgence of religion that spread to the Middle East and other parts of the world, including Africa.

Consequently, by the end of the 1970s, many of the scholars who predicted the demise of religion had recanted. Peter Berger wrote an important article on de-secularization. While Harvey Cox admitted that he was wrong. The resurgence of religion led to a renewed interest in investigating religion.

The 9/11 attack on the United States further recuperated religion in the world. As the world witnessed the near-collapse of America, the acclaimed superpower, following the terrorist attack, believed to have been led by Usama bin Ladin (founder of the pan-Islamic militant organization al-Qaeda), many turned to religion for hope.

The aftermath of the attack on the United States led to a revitalization of religious practices and scholarship.

A book that I enjoyed reading about the resurgence force of religion in the recent world was co-authored by an atheist and a Catholic (Adrian Wooldridge and John Micklethwait). The title of the book is: God is back: How the global rise of faith is changing the world. when I read the book, the questions I asked was: did God actually go anywhere? Do we determine when He is present or absent?

Notwithstanding these questions, the revitalization of religion did not affect only Christianity and Islam. It impacted on neo-traditionalization. In the 1980s in Ghana, Dr Ɔsɔfo Ɔkɔmfo Damuah Vincent Kwabena Damuah, a former Roman Catholic priest, founded the Afrikania Mission. His goal was to revitalize indigenous religions in Ghana.

Given that he was a member of the Provisional National Defence Council (PNDC) government, headed by chairman J.J. Rawlings, he had a near-monopoly over the state media to advance his religion.

The interesting aspect of the resurgence of religion globally is that it increased atavism for merging the spiritual and material worlds. It brought back witchcraft in the western world as a craft to study and practice as a profession, not an evil to exorcise.

Similarly, in 2019, there was a news item about the process of “de-sacralization” and “de-mystification” of witchcraft as a subject of study at the Venda University in South Africa.

But in all of this, there is no uniform and stable definition of witchcraft or who a witch is. Probably because it is an esoteric practice, much of what is known about it is speculative and the occasional, hysterical confessions of alleged witches.

In many cases, the confessions of alleged witches tend to confirm the beliefs built around the practice. More importantly, it helps Pentecostals and neo-Pentecostals to affirm and denounce the spiritual forces of indigenous religions.

It also brings the practices of the Pentecostals closer to indigenous religions. Professor Birgit Meyer in her article, “Make a complete break with the past”, has, for instance, observed that:

The proponents of Pentecostalization stood much closer to traditional worship than they themselves were prepared to acknowledge. Exactly because they regarded the local gods and spirits as really existing agents of Satan, they strove to exclude them with so much vigour, thereby placing themselves in the tradition of ‘Africanization from below’ which was developed by the first Ewe converts and which had much in common with African cults propagating radical cleansing (Meyer, 1998:319).

Among some of the Twi-speaking people, the word for a witch is “Obeifoɔ” which is believed to be a contraction of “ɔbre yie die ase fo” to wit, “someone or a group of people whose actions undermine progress.”

This definition leaves the reasons for witchcraft open and fluid. For example, anyone who may not possess witchcraft, but engages in anti-social activities could be labelled as a witch. In the same way, anyone who really possesses some form of spirit and is believed to be causing havoc is also considered a witch.

But sometimes the index used to identify a witch is so nebulous that anyone who performs incredibly in a particular profession could be termed a witch. For example, European inventors are considered to be witches.

Great footballers are said to be witches. Professor Onyinah gave an example of Opoku-Afriyie, a Ghanaian footballer, who was nickname “bayie” for his agility in scoring goals. A brilliant student, usually females, are easily tagged as witches.

Other anti-social practices may also lead to a person being classified as a witch. For example, someone who is stingy could be referred to as a witch. A person who is always alone could also be called a witch.

A person who sleeps late and wakes up late also qualifies to be called a witch. Other qualities like “excessive” “beauty” or “ugly” could qualify one as a witch. Excessive wealth and poverty are also marks of witchcraft. Given this, G.K. Nukunya, a Ghanaian professor of sociology, argued that the belief in witchcraft can socially function to ensure order in society.

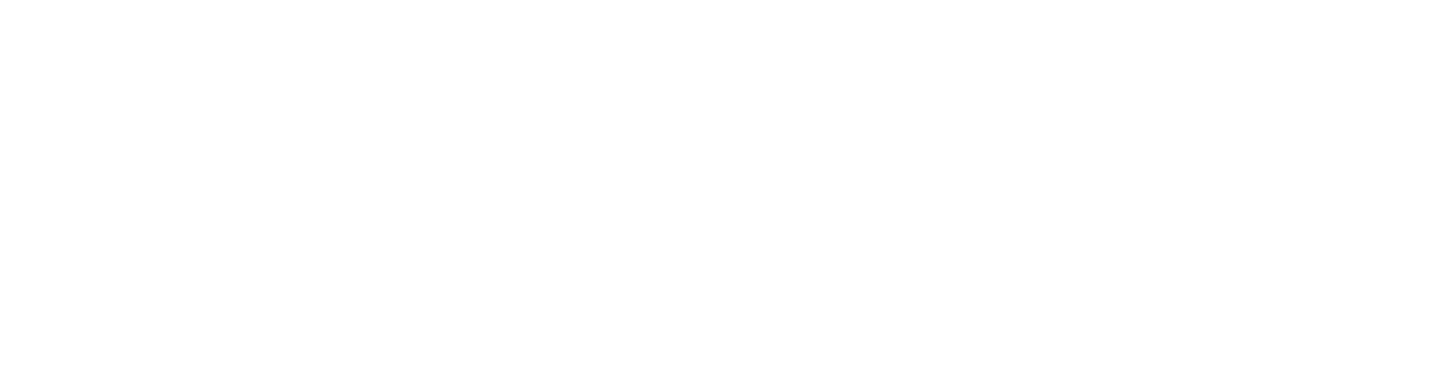

Unfortunately, the category of witches has been extended to include the aged. So, in the last few decades in Ghana, older women are easily tagged as witches. This could be because life expectancy is expected to be short in Ghana and so, if a woman crosses 70 years and starts to develop facial wrinkles, she is likely to be tagged as a witch. This is especially when her grandchildren begin to die while she is alive.

The other reason for branding and killing old women/men as witches/wizards may be explained by the lack of knowledge that as some individuals age, they experience some form of mental and physical degeneration.

A co-tenant of my family in Maamobi was so old that (probably over 90 years) that she was dried in the early mornings before 10 am. She forgot the names of her own children. She called them based on where one of them stayed. One of her children stayed at Kawokudi, also in Maamobi. So, she called her “Kawokudi”. And even when she had eaten, she would say she had eaten nothing and was starving.

It is partly because of the above that old women are lynched on the accusation of witchcraft. In November 2010, a 72-year-old Ghanaian woman, Ama Hemmah, was burned to death on suspicion of being a witch.

The killing of such vulnerable women may be daily occurrences, except that they are not reported. It is so sad that at a time when everyone expected to cherish old age as a signifier of wisdom, some inane individuals would kill the aged.

It was the supposed danger posed by alleged witches that camps have been created for them in some parts of Ghana. They are usually hedged from society. Their influence on their communities is allegedly curtailed as they stay in the camp under the leadership of a “witchdoctor” who is expected to exorcise them. As the alleged witches suffer social death and ostracization, they form a fictive family at the camps.

In 2011, I visited one of the so-named witch camps in Ngani in the eastern part of Yendi in the northern region of Ghana. I could not believe that women and a few men and children could be ostracized and labelled as witches. The camp was very deprived in many ways. No regular supply of water, no electricity and befitting sanitary facilities. I could not help but walk with a few of them to their small farms.

I joined them in their recreational activities, which included singing and dancing. At least, I could tell that even as encamped people, they could still find time to pursue recreation activities. I also realized that the camp was politically structured with leadership well laid out.

Some of them felt they were more at home in the camps than the villages where they had come from. Majority of the members of the camp were from the Northern Regions. But I found a few Akan women there, as well.

In all of this discussion, the other issue about witchcraft is the fact of modernity paradox. While modernity is tipped to end superstition, it appears to indirectly enforce it. In the world of social media, facilitated by speed internet connection, many of the youths of Ghana cherish more online activities than offline activities.

They prefer to have virtual friends, some of whom they would hardly meet for face-to-face conversation. For example, on July 16, I celebrated my birthday. I had over a hundred people writing to express their best wishes for me. But not a single one of them called me.

More dangerous with social media is the fact that most of us have become virtual beings. Our sociality and quest for offline social activities appear to be dwindling. Information is also freely shared on the internet. Most of the youths are more likely to ask for information from their peers on social media than their parents or grandparents.

We live in a time where parents and grandparents, especially those born before the advent of the internet (known as BBC – Born Before Computer) are forced to learn from their children. There is an inverse of the flow of education – most parents and grandparents now rely on their children and grandchildren for current information. The situation is perhaps worse for “illiterate” parents and grandparents.

Some social practices that invested the material for marriage (bridewealth) in the hands of the older generation, giving them control over the younger generation, has also almost disappeared. Through western education, most of the young men and women tend to secure jobs that empower them economically more than their parents and grandparents.

The implications of the above are very troubling for the future of older women and men in Ghana and elsewhere in the world. This is because we now live at a time where the inherent dignity of man (in the generic sense) has largely been substituted to “acquired dignity”.

This means that instead of human beings having inherent dignity because they are made in the image of God and needed to be treated with respect, we now see them based on their “utilitarian value”. We are defined by our functionality in society.

This also implies that if a woman cannot perform any role considered economically and politically significant, she is written off. The sanctity of human beings, conferred on them by God has been questioned. In the end, we “liquidate” people who we perceive do not contribute to productivity.

The future of old women and men and children with some form of physical or mental disability is very precarious. They do not only risk being branded and killed as “witches”, but they also risk being neglected. Most of them risk being socially ostracized.

The challenge pose by modernity is also such that as people get frustrated as they pursue the illusions of materialism that is displayed on social media and online outlets and suffer alienation in a fast-tract world, they are likely to vent their anger on the older generation.

As I conclude, I firmly believe that the Christian concept of God and man has the key to resolving the “liquidating” of people. The Biblical theology of God as the sovereign creator of the world implies that He is in charge of everything that happens.

This means that when we feel threatened by a malevolent spirit, we can trust Him for our ultimate protection. Second, as sovereign God, He determines the beginning and termination points of our earthly lives (Matthew 10:29). We don’t die until He wills it. So, Christians do not need to fear.

Third, the belief that man created in the image of God has important implications for protecting the “vulnerable” members of our society (Genesis 1:26). This is because the Bible categorically enforces the inherent value and dignity of every human being.

Every human being, therefore, has an inalienable right to life, happiness, protection, and prosperity (Genesis 9:6). The Bible holds that we are in the image of God, not in the image of production.

Let us all join hands to protect the vulnerable in society.

Satyagraha

By Charles Prempeh, Maamobi English Assembly.

Writer’s Email Address: prempehgideon@yahoo.com